Home > English version of HP > History of Saintonge, Aunis and Angoumois > Families and seigniories > Three generations of the Anglo-Poitou family of Vivonne, from 13th century (...)

Three generations of the Anglo-Poitou family of Vivonne, from 13th century “Poitevin mercenary captain” to 14th century “recalcitrant lady”

Three generations of the Anglo-Poitou family of Vivonne, from 13th century “Poitevin mercenary captain” to 14th century “recalcitrant lady”

Sunday 21 December 2008, by , 12001 visites.

All the versions of this article: [English] [français]

The following reconstruction of a 13th century Anglo-Poitou family is an illustration of how useful and encouraging internet sources can be.

"It is almost impossible to go very far in the study of our history without realising that our neighbours, ruled for so long by princes from France who also ruled some of our finest provinces, have archives containing masses of documents of interest to us ... [1]

In the mid 19th century the French historian Jules Delpit was sent to London on a thrilling mission – to locate and categorise documents in the English archives relating to French history. In the introduction to his work, Collection générale des documents français qui se trouvent en Angleterre, Delpit describes his astonishment when first confronted by bundles of ancient documents mouldering in old London basements. Today scholars are still working through the English archives, identifying, translating, analysing and preparing them for publication. Even better, much of their work is accessible on the internet - sometimes at such a rate that we can regularly look for and find newly published material that is often accompanied by scholarly discussion.

This story begins in 1220 during the aftermath of civil war in England when the Poitevin soldier, Hugh de Vivonne was in charge of Bristol castle. A serious conflict of interest had been growing between the Plantagenet kings and their Anglo-Norman nobles, and the more the king pursued a policy of reconquest on the continent – especially when it habitually ended in disaster - the more the Anglo-Normans felt used and abused. These descendants of 11th century Norman invaders were beginning to think of themselves as “English”, and the Poitou meant little more to them than a foreign, far-flung, unfamiliar place. The Plantagenets saw things differently. For Henry III kingship was a personal matter and as far as he was concerned his English and continental possessions were one and the same thing.

By 1215 the barons were already expressing their dissatisfaction, and two clauses in the Magna Carta had demanded the removal from England of Poitevin officials and all foreign knights and mercenaries. Then in 1258 the barons issued another petition demanding that only English-born men should hold strategic castles or marry English women. By this time, however, things had come to a head and Simon de Montfort, Henry’s brother-in-law led the 2nd baron’s revolt 1258-1265 that ended the king’s forty-two years of ‘personal rule’. [2]

Just at this moment, in 1259, Hugh de Vivonne’s son William de Fortibus died, leaving four very young daughters subject to the full impact of the Anglo-Norman feudal wardship system. On the death of a military tenant like William, the control of his estates reverted to the overlord, as did the marriages of any underage heirs, to be disposed of as he saw fit. This was enforced by the physical removal of child heirs from their family to be taken to the household of the overlord. In this way the king controlled his subjects’ loyalty as well as the monetary and military value of their estates, the system ensured a regular source of income, as well as a way to advance the careers of favourites or young knights. [3]

As we shall see, however, in the case of the Vivonne daughters the arrangement did not work as intended. Suddenly their story shifts from Somerset in England back to their grandfather’s original home in the Poitou. Eventually two of the granddaughters, Sybil and Mabel settled in France, [4] while Joan travelled between England and France, especially in her later years. Cecily, Hugh’s last surviving granddaughter may never have left England. She died in 1320, a few years before the first battles of the hundred years’ war. But by then the Vivonne family had exchanged their inheritances, separating those in France from those in England and Ireland - unlike the Plantagenets whose claims to the Aquitaine would only finally collapse after defeat in the war that for so long blighted English and French history.

The family of Joan, Sybil, Mabel and Cecily de Vivonne

Hugh de Vivonne (?-1249)

The few traces of Hugh de Vivonne so far found in French archives allow only an incomplete and tentative reconstruction of the Vivonne family and Hugh’s place it. [5] Fortunately, however, many traces of his career, his marriage, and even his letters, survive in the English archives.

Hugh supported the Plantagenet cause on the continent, and when he first made his mark in English history his situation was not to be envied. He may have arrived in England as part of a force of men under the command of Savaric de Mauleon that king John had called for. [6] On the death of king John in 1216 Hugh had been put in charge of Bristol castle, standing in for Savaric who had been called away to attend to John’s funeral. [7] He had not, however, been paid as promised for the castle upkeep, so when the Regent William Marshal ordered him to return the castle to Gilbert de Clare, earl of Gloucester, Hugh refused. In 1220 he explained this in a letter to Henry III, reminding the king that his loyalty to Henry himself and to his father John had cost him his own “rich and fertile lands” at home across the seas. [8] The fact that five years earlier Gilbert de Clare had been one of the Magna Carta rebels who invited the French prince Louis to invade England and claim the English crown must have made Hugh’s sense of grievance even more difficult to swallow.

After making this stand at Bristol there is no evidence that Hugh had any more outright political difficulty, even if he remained - for some - nothing more than “a Poitevin mercenary captain”. [9] On the contrary he went on to become a well-respected soldier and king’s officer. He did return home - but as Henry’s seneschal in Gascony and Poitou, and he was at Henry’s side during his campaigns there, including Taillebourg in 1242. [10]

His new home was in Somerset, holding several manors there by right of his wife Mabel Malet. He also acquired in his own right tenancies confiscated from families who had rebelled or otherwise displeased the king – as we shall see, the manor of Corston Denham granted to Hugh in 1246 had been held by the Saint Hilaire family and later claims by the Saint Hilaires for the return of the manor are particularly useful in establishing the Vivonne relationships.

Mabel Malet (c.1200-probably before 1248)

The Malet family had been close to the kings of England, both Anglo-Saxon and Norman, since before the Norman Conquest. Mabel’s ancestor William was a companion of William the Conqueror in 1066 who is thought to have died fighting the insurgent Hereward the Wake, and one of his sisters was the legendary Lady Godiva. [11] A great landowning family in Somerset, the Malets had sometimes held high office and had sometimes been rebels, and Mabel’s father William had himself experienced these uncomfortable about-turns in fortune. Having joined the rebels in 1215 his lands were confiscated but at some point they were restored either to him or to his heirs, Mabel and her sister Helowise.

For all the revenues his marriage would have brought him, however, Hugh could not or would not pay a debt of 2000 marks payable to the Exchequer that his father-in-law had owed to king John, and there are records in the Fine Rolls of how this and other debts were offset by his service in Gascony. [12] The archives in England for this period are littered with examples of the debt-ridden life the feudal system created for military tenants and their families, and Hugh was no exception.

William de Fortibus (?-1259)

Very few details about the life of Hugh’s son William have survived. For some reason, instead of using his father’s name he was usually referred to as “le Fort”, “des Forz” or “de Fortibus”. He had at least three younger brothers and sisters: Hugh and Helowise do not concern us here - nor, in any direct way, does his sister Sybil, apart from the challenge to her holding of the manor or Corston Denholm – see below.

When William married Matilda de Ferrers in July 1248 [13] he was probably in his early twenties, a fully trained knight and landowner in his own right having apparently inherited Mabel’s Malet estates. Two months earlier in April 1248 the king had given him permission to “to go to his own parts of Poitou and there acquire as best he can the lands belonging to him by inheritance through the death of Emery de Vivona, uncle of the said William, and hold those lands with the lands in England falling to him by inheritance.” [14] Presumably this Emery was Hugh’s brother, and possibly Hugh’s work as seneschal in Gascony and Poitou had allowed him to restore family ties.

The latest Fine Rolls published to 1255 show the classic accumulation of debts William took on once he had given the king the oath of allegiance required before he could take possession of his inheritances, taking over his father’s debts and then adding his own. We also learn, however, that on 5 July 1255 William had been with Edward the king’s son, in Gascony and that he remained there with the prince, his debts in respite, as his father had earned twenty years before.

It would seem that on his death in 1259 William had consolidated his legacies both on the continent and in England. Leaving his four young daughters as heirs, the lands they inherited straddled the domains of Henry III in both countries – the lands of Vivonne overseas, Hugh de Vivonne’s acquisitions in England, and his mother’s Malet estates in England.

Matilda (or Maud) de Ferrers (c.1230-1299)

Furthermore, the young daughters were also heirs to their mother’s Pembroke inheritance. William’s wife Matilda de Ferrers was related to many of the most powerful Anglo-Norman families in England. Of special note was her maternal grandfather, the same William Marshal who had ordered Hugh to hand over Bristol Castle twenty years earlier. Earl of Pembroke by right of his wife Isabel de Clare, William had begun life as a penniless and landless fourth son. He became a “knight errant” and made his own way in the world by seizing valuable hostages at melees. Thereafter he gave unflinching loyalty to the king even when, at one point, John confiscated all his estates. Aged about 70, he fought in full armour on horseback at the 1216 battle of Lincoln and until his death in 1219 he had been one of the three regents of the minority government of the boy king Henry III. [15]

One of the Marshal’s ten children was Matilda’s mother, Sybil Marshal who married William de Ferrers earl of Derby. They had seven daughters and when Sybil died, probably about 1238, the earl remarried and finally had a male heir, Robert. [16]

So Matilda, born probably in about 1230, one of seven daughters of a mother who was one of ten children, five of them sons, did not start out with a particularly promising personal inheritance in prospect. By 1245, however, that had changed dramatically and Matilda had become an heiress in her own right. In that year Anselm, the last of her five Marshal uncles, was dead and none of them left any legitimate children as heirs. Consequently, in 1245, the Pembroke estates were broken up to be divided between the Marshal sisters or their descendants like Matilda.

Some time in May 1248 when she was about 18, Matilda’s first, childless marriage ended with the death of her husband, Simon de Kyme. Two months later the king had granted her remarriage to William de Fortibus, and she swore her oath of allegiance. [17]

Eleven years later William had died and Matilda did not remarry for five years until in 1264 she contracted her third marriage to the recently widowed Aimery (IX) viscount de Rochechouart. [18] There is no evidence that Matilda and Aimery had any children together but this time her marriage lasted over twenty years until Aimery died in about 1286. The Calendar of Patent Rolls has several entries indicating that the couple travelled to and from England several times, the first in 1269 [19] naming lawyers presumably to deal with legal disputes and transactions concerning the Vivonne and Pembroke family estates in England.

Wards of Court, 1259 to 1264

When William died his daughters, Joan, Sybil, Mabel and Cecily, were made wards of court. They were probably taken to the king’s household since the family estates included military tenancies held of the king where they would be due to stay until they married. [20]

On 2 August 1259 a marriage each and a share in the custody of William’s estates in Surrey, Somerset and Devon (from which Matilda’s dower would be paid) were granted to four knights: Ingram de Percy, Peter de Chauvent, Imbert de Muntferaunt and Laurence son of Nicholas de Sancto Mauro.

Ingram had the marriage of the eldest daughter, then Peter de Chauvent could choose from the three others, and so on. Each man had the choice of marrying the ward himself or he could sell the marriage to someone else.

The guardians could only sell the marriage on, however, after giving the mother first refusal, allowing her to repurchase the marriage at the going rate - “Maud de Kyme, their mother, shall have preference over others if she shall wish to buy the said marriages, provided always that she give as much for them as others would”. But these marriages were valuable because of the property and career advancement through military service they represented. [21] The chances that Matilda could buy them back must have been slight.

Such was the situation in England. William’s daughters, however, were also the heirs to his Poitou estates of Vivonne. There the Anglo-Norman feudal system did not apply so the custody of the inheritance and decisions about the marriage of underage children stayed with the family, and in this case their guardian was Savari de Vivonne.

The question of who had the right to decide who should marry William’s daughters and acquire their inheritances - the king in England or the Vivonne family in the Poitou - must have been raised. Indeed the archival evidence shows that the king’s original arrangements did not proceed at all smoothly, and there is a series of entries in the Patent Rolls between 1259 and 1265 about the grants – repeating them, enforcing them, reinforcing and clarifying them - which is unusual. [22]

And the fact is only one of the marriages required by king Henry actually, and then only briefly, took place.

Joan (Jeanne) de Vivonne (c.1251-1314)

Some time during the summer of 1262 Joan was finally married to Ingram de Percy, but by 10 October Ingram was dead. Joan once again became a ward of court, this time her marriage granted to Henry’s queen, Eleanor of Provence. [23] Custody of Joan’s share of her father’s English estates passed, for the time being, to Ingram’s heirs.

After this, for nearly three years, there are no more entries in the available English archives about any of the Vivonne daughters. During this time, of course, there was the de Montfort rebellion and Henry III was even imprisoned, so any records that may have existed could well have been lost. Finally, however, in April 1264, the story is taken up in the archives of the Poitou family of de Rochechouart when Simon de Rochechouart (who was to become the archbishop of Bordeaux) announced that with the marriage contract between his nephew Aimery (IX) and Matilda, their two older children were also contracted to marry – Aimery’s two older sons to Mathilda’s two older daughters. [24]

The same contract settled two-thirds of the Rochechouart viscountcy on Aimery (X) who was to be the next viscount, and his brother Guy. For her part Matilda settled the Pembroke manor of “Carlion” (Caerleon, Wales) on Joan. A few years later, in 1268/9 Aimery and Matilda exchanged Caerleon for the manor of Kilsmersdon in Somerset, presumably on Joan’s behalf.

A fortnight or so after Simon’s announcement of the marriage contract, Savari de Vivonne transferred to Aimery (IX) “all the rights held by the daughters of the late William de Vivonne, seigneur de Fors, whose wardship and custody he held, in all the land and properties of Vivonne.” [25]

No Vivonne or Malet estate in England is mentioned in these announcements from Rochechouart, so it looks as though queen Eleanor passed Joan’s marriage wardship to Savary de Vivonne separately from her estates in England, leaving the question of who had custody of those estates unresolved. As late as 8 November 1265 Ingram de Percy’s will was confirmed and custody of the estates passed to Ingram’s brother William. By December, however, William de Percy had also died and there is no evidence indicating that the Percys had custody of the estates.

The next piece of evidence appears in the Somerset Pleas for 1269 and concerns the manor of Corston Denham that Hugh de Vivonne had settled on his daughter Sybil, wife of Anselm de Gourney (mentioned above). In that year Peter de Saint Hilaire began a long campaign to reclaim the property and the Somerset Pleas record that "Emery de Roche Chaward", his wife Joan and her sisters Sybil, Mabel and Cecily were required to appear to answer the claim. This is the only documentary evidence found so far in the English archives that mentions Joan’s marriage to Aimery (X) de Rochechouart. [26]

His claim having failed in 1269 Saint Hilaire tried again in 1280, but this time the records show Joan to be the wife of the ageing knight, Reginald FitzPiers. Genealogies of FitzPiers state that Reginald was her second husband but as we see this is not the case - her second husband was Aimery (X) de Rochechouart. [27]

Unfortunately there is as yet no trace either of the date Reginald’s first wife Alice de Stanford died, or the date of his marriage to Joan. Aimery (IX) made his will in 1283 before going overseas in the service of the king stating that his son Aimery (X) was dead and that his successor was his grandson, Aimery (XI). It had been presumed that Aimery (X) had died in or about 1283, but as Joan was already married to Reginald FitzPiers in 1280, Aimery (X) must have died in that year at the latest, probably earlier.

The final entry in the French archives concerning Joan is a 1304 agreement between Aimery (XI) and his sister Jeanne. In this it appears that Joan was receiving a dower of 200 “livres” from the viscountcy of Rochechouart that would transfer to Jeanne “after the death of their mother, Jeanne de Vivonne”. [28]

After Reginald’s death in 1286 Joan spent much of her time in France as we can see from entries in the Patent Rolls for 1290, 1292, 1301, and 1307 - she would by then have been in her late fifties. In all probability, Aimery (XI) and Jeanne had been born during the first part of the 1270s in which case there was plenty of time for her to marry FitzPiers and have children by him before he died.

Although they both married, neither Aimery (XI) or Jeanne had children, and on Aimery’s death in 1306 the viscountcy passed to his uncle, Simon.

Sybil de Vivonne (c.1253-before 1313)

While we know that in 1259 Ingram de Percy was allocated Joan’s marriage and that Peter de Chauvent chose Cecily’s marriage, (see below), all we know about the marriage chosen by Imbert de Muntferrant is that it was one of the other two daughters. Whether it was Sybil or Mabel, however, it no more went to plan than the others.

A Patent Rolls entry for 10 May 1262 discusses Imbert’s decision to sell his custody of both the estates and the marriage of the daughter he had chosen. The king agreed to this but added that if Matilda did not buy the marriage from Imbert or from the person he sold the marriage to, it could be sold on as he saw fit, on condition that it was without “disparagement of the said girl”, [29] that is, to someone of lower rank, or to a foreigner, in particular a Poitevin.

However, Sybil went to the Poitou and did marry a Poitevin, Guy de Rochechouart, as required in the 1264 marriage contract between their parents. We know this marriage took place but not when. The 1269 entry in the Somerset Pleas suggests that in that year there had been no marriage as, unlike for Joan, no husbands for Sybil or her younger sisters are noted. According to the Rochechouart archives, Guy and Sybil had married before 1279 and this is confirmed in the 1280 Somerset Pleas when the names of all four daughters are given with those of their husbands.

It looks as though the legal processes for the exchange of the rights of Sybil and Cecily to their inheritances had begun before 1279. This involved their father’s estates in Vivonne and Poitiers and later on, after Matilda died in 1299, those of their mother in England, separating them according to where they lived. Unfortunately it is not yet possible to identify the English place names given in the Rochechouart archives for Sybil’s holdings – “Dusselinghe, Cambridgeshire” and “Walneton, Dorset”. That estates from Mathilda’s Pembroke inheritance were exchanged however is confirmed by the Patent Rolls of 22 June 1301 noting the grant made by Sibyl and Guy de Rochechouart to Cecily and her husband, John de Beauchamp, and the next day this grant is identified as Sibyl’s share of the Pembroke estate of Luton, Bedfordshire. [30]

When Guy died in 1313 he had remarried. Other than this indication that Syil was still alive in 1301, no date for her death is known.

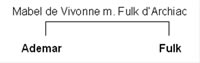

Mabel de Vivonne (c.1255-before 1299)

Evidence for Mabel’s marriage to Fulk d’Archiac is the same as for her sisters - the records of court procedures dealing with their Somerset estates and various entries in the Patent Rolls. In the Somerset Pleas of 1269 she was still single but in 1278 Fulk established his claim to the manor of Woodmansterne, Surrey by right of his wife, with one third was held by Matilda in dower. [31] Mabel and her husband Fulk d’Archiac are also recorded in the Somerset Pleas of 1280. There is another mention of them both in the Patent Rolls in 1291, but in 1294 only Fulk is mentioned. So Mabel had probably died by then – if so she was the only daughter who did not survive her mother.

All available records of the transfers of Mabel’s title to her estates in England show they were made by her sons. An inquisition of 1304 after Fulk’s death confirmed that Aymer d’Archiac (born about 1279) was Mabel’s son but as he had been born abroad he had to prove his age before the king would accept the oath of allegiance required before he could hold the manor. This was duly done and four years later in 1308 Aymer paid the duties for the transfer to “Joan de Vivonne” of at least some of his rights to the Vivonne/Malet lands in England, and to the Pembroke lands in England and Ireland. There is no evidence of what Joan presumably transferred to Aymer in exchange. [32]

This would confirm how the separation of the daughters’ four equal shares in their inheritance was done – first into two parts, Joan’s and Mabel’s on the one hand and Sybil’s and Cecily’s on the other, thereafter the division was made between the two sisters in each grouping according to where they lived. But there are many inconsistencies in the available records in England that make the results difficult to unravel.

There is evidence, for instance, that first Aymer d’Archiac, then when he died, his brother Fulk, wanted to keep, or have the right to sell, the manor of Woodmansterne in Surrey and the manor then became the subject of a prolonged dispute between Fulk and his aunt Cecily de Beauchamps. [33]

Cecily de Vivonne (c.1257-1320)

In 1262 Cecily’s marriage had been given to Peter de Chauvent, but the next time we hear about her is in 1265, so aged about 8. She had “long” been in the “keeping” of the king’s daughter-in-law, Eleanor of Castille, wife of the future Edward I, and Eleanor wanted to be paid for the cost of Cecily’s keep, so the king granted her custody of Cecily’s Vivonne/Malet inheritance which had till then presumably been with de Chauvent. [34] It seems likely, therefore, that is was Eleanor who arranged Cecily’s marriage to John de Beauchamp of Hacche Beauchamp, Somerset. They probably married in 1273 when Cecily would have been about 16. John died in 1283 leaving two sons, John and Robert. Cecily would still have been a young women but she never remarried; she survived all her sisters, and seems to have spent much of her forty years of widowhood acquiring property.

Legal disputes and challenges often surrounded these acquisitions leaving many traces of Cecily in the archives. Still in her twenties, a 1286 entry in the Register of the Abbey of Athelney, Somerset notes her dealings with the Abbot of Athelney:-

“The lady Cecilia de Beauchamp has found pledges, Robert de Ashford, etc. for saving her default before the date of the next court, or that she will come to the Abbot of Athelney, and there save it, as appears in the Hock-term Court (roll) of 14 Ed. I (1286)”

It is tempting to find in the archives echoes of the determined character of Cecily’s forebears – as a note in the Register quoting the 16th century historian, William Camden, shows:

“This recalcitrant lady was the widow of John Beauchamp I, who died at Hatch 24 October 1283. She was the second daughter of William de Vivonia (de Fortibus) and Matilda de Kyme his wife, who to quote the words of Camden “derived descent from Sibilla, co-heiress of William Marshall, that puissant Earl of Pembroke, William de Ferras, Earl of Derby, Hugh de Vivonia, and William Malet – men of great renown in ancient times”. And what is more to the point, she brought her husband a share of the barony of De Fortibus. The Abbot evidently had a hard struggle with this daughter of a hundred Earls to acknowledge his superior position in the manor of Ilton.” [35]

Records in the National Archives relate how Cecily also took on the earl of Kildare in Ireland, and the sheriff of Surrey. She seems to have won her legal battles so that by the time she died she had accumulated a large landed fortune for her de Beauchamp descendants.

As we have seen, Cecily spent much of her childhood and youth in the household of her guardian, the future king Edward I’s wife, Eleanor de Castille. Possibly this close association with the royal family influenced the way the four daughters marriages were arranged, apparently in favour of the de Beauchamp family. By 1284 Cecily already held more manors from the de Fortibus’ Somerset estates than the quarter share she had inherited on William’s death in 1259, holding most of the Glastonbury abbey tenancies listed as de Fortibus estates. Aimery (IX) de Rochechouart and Matilda are noted as having dower in Cecily’s manor of Shepton Malet and also in Joan’s Midsommer Norton estate, while Joan and Reginald FitzPiers held Chewton. [36] Normally we would expect to see William’s estates to be distributed more or less equally between the four daughters or, if Sybil and Mabel had already exchanged their shares, an equal division between Joan and Cecily, but this is not the case.

This discrepancy suggests the possibility that the guardianship and marriages of the Vivonne daughters may have been settled at some point with parts of the quarter shares due to Joan, Sybil and Mabel. If so this would confirm that Cecily’s marriage and her share of her father’s inheritance were used to extract the Vivonne daughters from the original wardships of 1259, and to bring about the safe repatriation of the Vivonne lands to Poitou.

The final episode traced in the available archives about the Vivonne daughters concerns the prolonged dispute between Cecily and her Archiac nephew Fulk (II) over the Surrey manor of Woodmansterne. As noted above as early as 1278 his father, Fulk (I) d’Archiac had established his claim to Woodmansterne by right of his wife Mabel, and the 1304 inquisition held on Fulk (I)’s death accepted his son Aymer’s claim. Both Fulk (I) and his son Aymer had died by 1314 so his second son Fulk (II) succeeded to the manor.

Cecily, however, successfully claimed it for herself and obtained a writ of entry against Fulk dated 4 August 1314. But the following year she complained to the king that she had been thwarted by Sir William Inge, chief justice of the King’s Bench, accusing him of acting in collusion with Fulk. Inge, she said, had altered the date of the writ from 4 to 14 August, and during those ten days Fulk had sold him the manor. Apparently Inge was dead by this time and her complaint was accepted, so when she died five years later, it was Cecily who held the manor of Woodmansterne.

Sources

Most sources used are available on the internet, but some are still only available in printed form. The Histoire de la Maison de Rochechouart has just been republished (October 2008) in facsimile. The records vital to this reconstruction in the Somersetshire Pleas and the Register of the Abbey of Athelney were found in Somerset public libraries by Reg Schooling.

Athelney Register of the Abbey of Athelney Public Library, Street, Somerset

BH British History Online http://www.british-history.ac.uk

CPR Calendar of Patent Rolls – courtesy of the University of Iowa http://www.uiowa.edu/ acadtech/patentrolls/

Feudal Feudal Aids A.D. 1284-1431. Inquisitions and Assessments ....... —http://libsysdigi.library.uiuc.edu/...

FMG Foundation for Medieval Genealogy, Medieval Lands http://fmg.ac/Projects/MedLands/Int...

FR Between Magna Carta and the Parliamentary State: The Fine Rolls of King Henry III 1216-1272 http://www.finerollshenry3.org.uk/c...

HMR Histoire de la Maison de Rochechouart by Général Comte Louis-Victor-Léon de Rochechouart, Imprimerie Christian LACOUR-OLLE, Nîmes. www.editions-lacour.fr

Marshal William Marshal, Knight-errant, Baron, and Regent of England, by Sidney Painter, Toronto University, 1982 http://books.google.com/books?id=i9...

Royal Royal and other historical letters illustrative of the reign of Henry III, selected and ed. by W.W. Shirley, published by Kraus Reprint, 1862, Google Books

SdM Savarie de Mauleon by H.J. Chaytor, CUP Archive, Google Books

SP Somereset Pleas, Yeovil Public Library, and Street Public Library, Somerset

Trokj The reign of king John, by Sidney Painter, Ayer Publishing, 1979, Google Books

[1] Collection générale des documents français qui se trouvent en Angleterre, by Jules Delpit, 1847, p.i

“Il est bien difficile de faire une étude approfondie de notre histoire sans songer que les archives d’un peuple voisin, longtemps gouverné par des princes d’origine française, et possesseurs à ce titre de quelques-unes de nos plus belles provinces, doivent nécessairement contenir une foule de documents intéressants pour nous ........ “

[2] Two recent works on this subject are accessible on on a limited basis on Google Books!- The Struggle for Mastery: Britain, 1066-1284, by David Carpenter, OUP, 2003; Peter des Roches – An Alien in English Politics, 1205-1230, by Nicholas Vincent, CUP

[3] For a fuller account of this system see http://www.historycooperative.org/j... p.36

[4] Despite all the evidence that William de Fortibus and Matilda de Ferrers had four daughters this is rarely noted in accounts of this family. English accounts often give only two daughters – Joan and Cecily. French accounts usually mention only Joan (Jeanne) and sometimes Sybil. In the Rochechouart archives there are “at least three” daughters. This present article explains how the different destinies of the four daughters, whether they married on the continent and settled there, or not, has led to this confusion.

[5] FMG Aquitaine Nobility

[6] Trokj p. 299

[7] SdM p. 37

[8] Royal, p. 90

[9] BH Dullingham manor

[10] Royal

[11] FMG Aquitaine Nobility, and for a fuller account of the Malet family see http://www.mallettfamilyhistory.org...

[12] FR

[13] CPR Henry III, vol. 4, p. 23

[14] CPR Henry III, vol. 4, p. 13

[15] Marshal, p.249. Painter’s account of Marshal’s life is based on L’Hstoire De Guillaume le Marechal

[16] FMG England, earldoms created 1138-1143. Robert’s first wife was Marie de Lusignan

[17] CPR Henry III, vol. 4, p. 23

[18] HMR Vol.II p.282 “Rochechouart (messire Simon de), doyen de Saint-Antregil du château de Bourges, notifie par ses lettres du lundi après la Saint-Georges, 1264, que par le contract de mariage de noble homme Aimery, vicomte de Rochechouart, son neveu, avec noble dame, Matilda, veuve de noble homme messire Guillaume le Fort, .......”

[19] CPR Henry III, vol. 6, p. 316

[20] A thorough account of wardship is available at http://www.historycooperative.org/j...

[21] CPR Henry III, vol. 5, p. 36

[22] CPR Henry III, vol. 5, p. 38, Henry III, vol. 5, p. 146, Henry III, vol. 5, p. 205, Henry III, vol. 5, p. 212, Henry III, vol. 5, p. 499 - 500

[23] CPR Henry III, vol. 6, p. 735

[24] HMR Vol.II p.282 ...... il avoit été conclu un mariage des deux fils du dit vicomte avec les deux filles de la dite dame veuve, et qu’il avoit été réglé qu’Aimery, fils aïné, épousant la fille aïnée de la dite dame, auroit la vicomté de Rochechouart et que Guy, autre fils du dit vicomte, épousant la seconde fille, auroit la terre de Mortemar , et que ladite dame donneroit son manoir de Carlion de préciput à sa fille aïnée, et enfin, que lesdits deux fils du vicomte auroient les deux tiers de l’hérédité d’iceluy vicomte; l’autre tiers demeurant pour le partage de ses autres filles et fils.”

[25] HMR Vol.II p.282 “Noble homme, messire Savary de Vivonne, chevalier, cedda à noble homme, messire Aimery vicomte de Rochechouart, tous les droits que les filles de feu messire Guillaume de Vivonne, seigneur de Fors, dont il avoit la garde et tutelle, avoient en la chatellerie et toute la terre de Vivonne. Par acte du mardi après la translation de saint Nicolas, 1264”.

[26] SP July 1269 pp. 96-97 “And Aunsell de Gurnay and Sibyl came and vouched to warrant them therein Emery de Roche Chaward, son of Emery de Roche Chaward, and Joan his wife, Sibyl, Mabel and Cecily, the daughters and heirrs of William de Fortibus.”

[27] SP 1280 pp.8 – 9 “The assize comes to recognise whether Henry de Sancto Hillario, uncle of Peter de Sancto Hillario was seised in his demsene as of fee of a messuage and two carucates of land in Coreston on the day which etc. and whether etc. which Anselm de Gurney and Sibyl his wife hold, who come: and they vouch to warranty thereon Reynold fitz Peter and Joan his wife, Guy de Rupe Cawardi and Sibyl his wife, John de Beauchamp and Cicely his wife [and] Fulk de Archiaco and Mabel his wife, the heirs of William de Fortibus. Let them have them here on the morrow of S. John the Baptist, by aid of the court. And let Reynold and Joan his wife, Guy and Sibyl his wife, John and Cicely be wife be summoned in county Somerset and Fulk and Mabel his wife in county Surrey.”

[28] HMR Vol.II p.291 ”Noble homme, messire Aymery, vicomte de Rochechouart, chevalier, fit un accord avec Jeanne de Rochechouart, sa soeur, par lequel il luy cedda, pour son partage des biens de la succession de feu messire Aimery, vicomte de Rochechouart, leur ayeul, de l’avis de Foucaud de Rochechouart, doyen de Bourges, seigneur de Saint-Auvent, Guy de Rochechouart, seigneur de Tonnay-Charente, et Simon de Rochechouart, seigneur de Saint-Laurent, chevaliers, leur oncle : 100 livres de rente sur la vicomté de Rochechouart, autres cent livres de rente sur la même vicomté, après le décès de Jeanne de Vivonne, leur mère. Par acte de mardi après Saint-Hilaire, 1304, en présence de Pierre de Verneuil, chevalier, et autres.”

[29] CPR Henry III, vol. 5, p. 212

[30] CPR Edward I, vol. 3, p. 599

[32] CPR Edward II, vol. 1, p. 147

[34] Henry III, vol. 5, p. 415

[35] Athelney

[36] Feudal

Histoire Passion - Saintonge Aunis Angoumois

Histoire Passion - Saintonge Aunis Angoumois

Forum posts

1. Three generations of the Anglo-Poitou family of Vivonne, from 13th century “Poitevin mercenary captain” to 14th century “recalcitrant lady” , 21 September 2009, 21:26, by CW Bingley

Heloise de Vyvonne was the second wife of Walter Baron de Wahul[Wodhul] By his first wife Walter had a son who inherited the Barony. They were descendants of Count Eustace of Boulogne by his son Lanmbert de Lens.

According to English records there was no issue - however Heloise’s coat of arms appeared later in Scotland - Gules[Boulogne]3 buckles [Malet]on a fess over a bend checky argent and azure [La Marche] It belonged to a family named Woddal. Now they are called Waddell

1. Three generations of the Anglo-Poitou family of Vivonne, from 13th century “Poitevin mercenary captain” to 14th century “recalcitrant lady” , 26 September 2009, 09:10, by Margaret

Thank you for this note about Hugh de Vivonne’s daughter Heloise.

However, according to

http://www.british-history.ac.uk/re...

she was not Walter’s second, but his only wife, and so the mother of John de Wahull.

Because of the apparent distance of this branch of Hugh’s desendents from his Poitevin origins, I haven’t followed it up. But perhaps it would explain why Heloise’s coat of arms turn up later in Scotland?

If I understand the coat of arms correctly, Boulogne and Malet would have come together with the marriage of Heloise and Walter, but do you know where the La Marche (Lusignan?) element comes from?

Margaret

2. Three generations of the Anglo-Poitou family of Vivonne, from 13th century “Poitevin mercenary captain” to 14th century “recalcitrant lady” , 30 September 2009, 16:05, by CW Bingley

I have, from old pedigree in Bedford Record Office about 20 years ago

Walter de Wahul d1269

Walter de Wahul d1269

= 1 Argentinia de Welton [Weton/Welton family

from Roger de Bucy? also married into de Nowers

family see Uvadale] issue John de Wahul,

Beatrice de Wahul = Henry Fitznorgold

=2 Heloise de Vyvonne no issue shown

3. Three generations of the Anglo-Poitou family of Vivonne, from 13th century “Poitevin mercenary captain” to 14th century “recalcitrant lady” , 13 November 2009, 21:02, by CW Bingley

I have since discovered that Heloise de Vyvonne’s son Lord John de Wahul married an Agnes daughter of Lord Henry de Pinckenay, Baron de Weedon and his wife Alice daughter and heiress of Sir David Lindsay III of Crawford, ggson of King William ’The Lion’ of Scotland. The original coat of arms of the Lindsey family is red with a fess checky Ar and Az indicating their descent from the Counts of Alost. So my hunch about La Marche was wrong C W Bingley

4. Three generations of the Anglo-Poitou family of Vivonne, from 13th century “Poitevin mercenary captain” to 14th century “recalcitrant lady” , 16 November 2009, 16:50, by Margaret

Thanks very much for the information * I’ll update by records. Hunches are always worth following, aren’t they, and even if wrong often lead on to other good stuff.

Margaret

5. Three generations of the Anglo-Poitou family of Vivonne, from 13th century “Poitevin mercenary captain” to 14th century “recalcitrant lady” , 17 February 2010, 11:38, by CW Bingley

Further research has shown that Marjorie was a sister of King William ’The Lion’- so daughter of David of Huntingdon Records of the claimants for the Scottish throne] CW

6. Three generations of the Anglo-Poitou family of Vivonne, from 13th century “Poitevin mercenary captain” to 14th century “recalcitrant lady” , 12 October 2010, 14:42, by M Brice

Hi I am researching my family tree of BERMINGHAM and ODELL in SHANAGOLDEN LIMERICK IN IRELAND.I happen to see your note re old pedigree from Bedford office.Would you be so kind if possible to forward, assist me the information,copy of the family surnames on the pedigree etc.I do appreciate any help.Thank you M Brice, AUSTRALIA.

marcusomega47@netspace.net.au

2. Étienne Contant (Content), de Burie ou de Migron, émigre au Québec au 17ème siècle, 14 November 2009, 16:41, by Paul Martin

je pense que Etienne Contant venait effectivement de Migron où des Contant sont encore rescencés dans les tables décennales de Migron en 1889. Il a dû se déclarer (ou être déclaré) "de Burie" par commodité, Burie étant plus connu que Migron, au Rgt de Poitou où son engagement n’a rien d’anormal, les Rgts changeant souvent de garnison à cette époque.

Paul-Louis

PS ma famille remonte à Etienne Martin (pas d’archives antérieures à 1674 à Migron), domicilié aux Coutant de Migron, mais je n’ai pas trouvé de cousinnage avec la lignée de notre ami canadien

1. Étienne Contant (Content), de Burie ou de Migron, émigre au Québec au 17ème siècle, 16 November 2009, 00:54, by Alain Contant

Cher Paul-Louis Martin,

Merci pour votre envoi récent au sujet de l’ancêtre Étienne Contant et du lieu de son origine, Burie comme il l’a dit dans plusieurs actes, ou Migron où il y a un hameau Chez Contant et une route des Contant y menant.

Je suis à terminer la recension des BMS des paroisses environnantes et il est clair qu’il n’y avait pas de Contant à Burie mais beaucoup à Migron. Votre envoi va me forcer à conclure, alors merci beaucoup.

Alain Contant

avocat retraité

3. Three generations of the Anglo-Poitou family of Vivonne, from 13th century “Poitevin mercenary captain” to 14th century “recalcitrant lady” , 17 January 2010, 20:44, by CW Bingley

One always finds more! Agnes de Pinckenay b 1149 had another husband with whom she had issue - Bernard de Balliol II 1140-1194